Shame, Pride, and National Identity: Confronting the Past

Article by: Presley Frank / Graphic by: Jillian Hartshorne

History Q2: Should anyone be ashamed of their nation's history? Should anyone be proud of it?

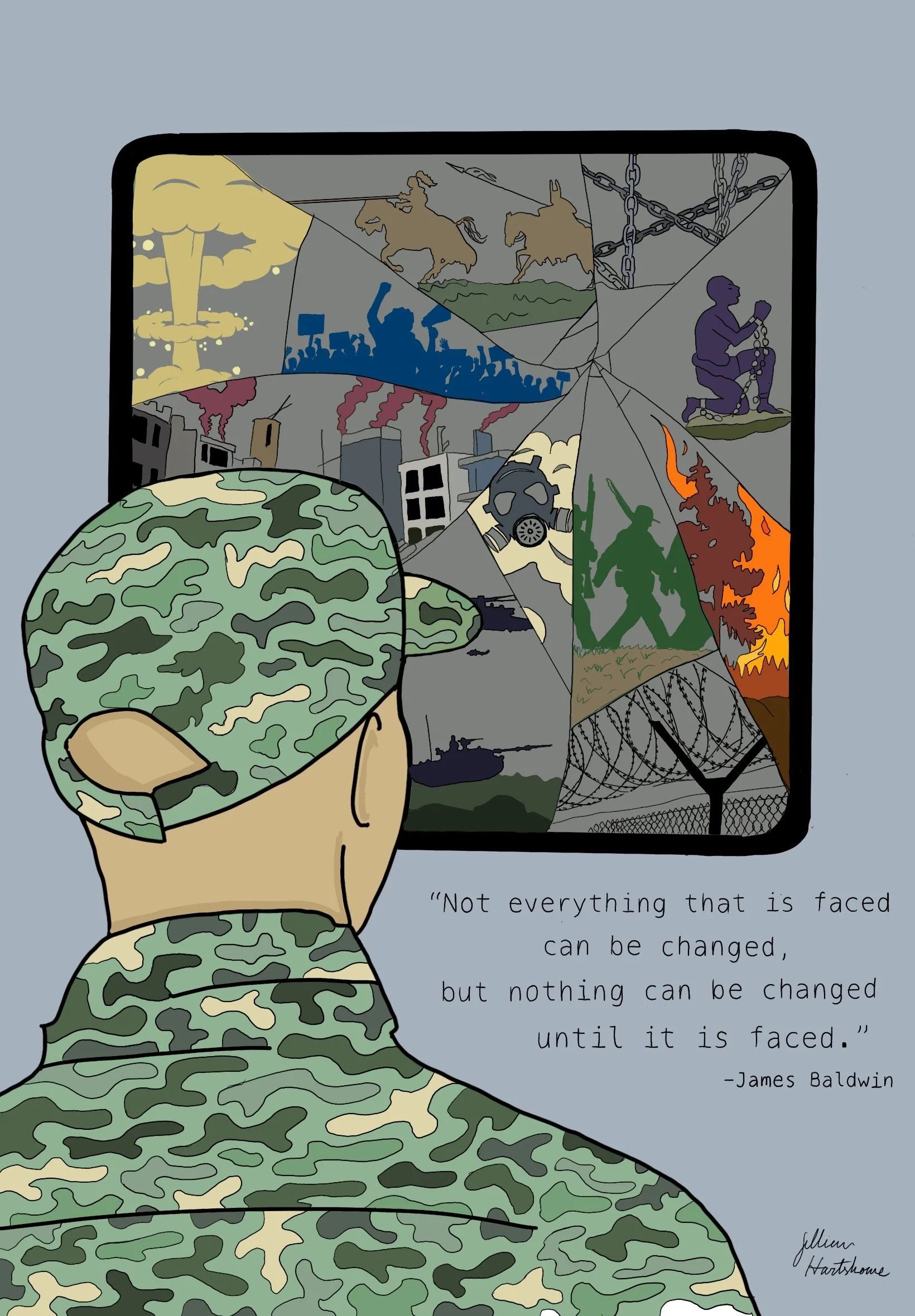

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” - James Baldwin

The emergence of nationalist ideology in the eighteenth century, notably through the American and French revolutions, marked a pivotal period in global history. These revolutions sought to escape a corrupted political rule and establish a new declaration of both politics and life. In this context, nationalism serves a justified purpose in advancing and preserving a nation as it binds people together to a common goal and purpose. Furthermore, a collective appreciation by society for its nation cultivates a sense of belonging. However, this shared identity becomes complicated when the same historical narratives that elicit national pride are rooted in injustice and inequity. While national identity and pride may offer the foundation for unity, pride in any nation relies upon an honest engagement with its history. To engage honestly with national history, we must examine revolutionary nationalism, imperial legacies, and the politics of history. Ultimately, shame in one's national history does not right past wrongs, and responsible pride in one's nation can only exist when accompanied by an accountable and holistic reflection of the past and commitment to promoting progress for the future.

The American and French Revolutions highlight the gap between proclaimed ideals and historical realities. Americans declared that "all men are created equal" while simultaneously upholding the institution of slavery, dispossessing Indigenous peoples of their rightful territories, and denying women's rights. This fundamental paradox is a deliberately sustained pattern of persistent oppression, exclusion, and abuse of power throughout American history. Similarly, the French Revolution's rallying cry "Liberté, égalité, fraternité" was directly followed by the Reign of Terror, a period of state-sanctioned violence during the French Revolution, in which citizens suspected of 'counter-revolutionary' activity were arrested, tried, and often executed without due process. Even so, oppressive colonial expansion, which imposed French rule across territories in Asia and Africa, revealed the fundamentally aspirational nature of nationalism. Proud citizens of new or renewed nations celebrated and professed great faith in the ideals they claimed to represent—liberty, brotherhood, equality, and freedom—rather than in the realities of their societal practices.

Nations like America and France take pride in their potential and what they will become while neglecting the lived realities of the people whom they oppress. This manipulation of history sets a dangerous precedent: a nation's ideals may proclaim one thing but allow societal practices and behaviors to contradict them entirely and still take pride in this falsehood. Leaders strategically used these myths to deflect criticism of national failures rather than taking accountability, revealing the dangerous nature of manipulation. American exceptionalism, for example, is rooted in the belief that America is exemplary in comparison to other nations, and proponents of such ideology employ revolutionary-era rhetoric to negate criticism regarding historical and present-day injustices. French leaders alike use republican ideals and values to suppress objections to colonial brutalities. America and France's manipulative approach to national pride reveals the tension between a nation's ideals and its society's behaviors, which grows more precarious as nations foster a misguided sense of pride based on myth rather than historical reality.

The imperial era demonstrates the complex relationship between violence, exploitation, and the mythological nature of national pride. In India, the British imposed restrictive economic policies that crushed the economy and drove society into famines while violently silencing all forms of resistance to the corrupt system. The British Empire maintained its imperial control and power through its dominance over global trade and its significant military presence. This pattern of imperialism is evident in the histories of the Belgian Congo and French Algeria, where "civilizing missions" were employed to justify dominance over other nations. The Belgian Congo, led by King Leopold II, spearheaded one of the most brutal massacres in colonial history, where Congolese people were forced into harsh labor systems and routinely mutilated and killed to meet labor expectations. Similarly, in French Algeria, pride in republican ideals conflicted with the brutal colonial realities faced by native Algerians as they were denied citizenship, systematically oppressed, and killed. While these empires fostered pride in their triumphs and behaviors as a people, then and now, their historical legacies are nonetheless marked by brutal, violent conquest, exploitation, and oppression. Pride often relies on fabricating history through the erasure of marginalized narratives and the lived experiences of colonized individuals and groups, illustrating history as merely a myth or story to uphold to maintain pride and avoid accountability. The legacy of imperialism demands acceptance of faults and commitment to truth, not glorification and ignorance, for the sake of false and hypocritical pride.

The consequences of failing to reckon with the past bleed into the present day as nations struggle to reconcile pride with historical accountability. In the United States, educational debates over critical race theory, slavery, indigenous genocide, forced assimilation, and removal reflect the refusal to acknowledge historical truths. The South's lost cause mythology, upheld as a valid national story by many Americans and set in school curricula, offered a narrow perspective of the American Civil War era by excluding African American experiences and perpetuating a fabricated lie. Similarly, Japan struggles with the present-day acknowledgment of wartime atrocities committed during the Second Sino-Japanese War, most specifically the Nanjing Massacre, the brutal massacre of Chinese civilians and non-combatants. Japan, while having issued an official apology for the massacre, continues to deny and minimize its scale of violence and impact by debating over death tolls and the naming of the event.

In contrast, Germany serves as a model of historical shame, guiding responsible pride as it attempts to build national pride rooted in truth. Vergangenheitsbewältigung, meaning "coming to terms with a past," is a holistic political process that actively addresses political practices (speech and action), compensation, and education. This framework reveals how Germany sustains a national identity upheld by historical responsibility following the atrocities of the Second World War. Contrarily, people have criticized South Africa for its ineffective strides toward acknowledgment of Apartheid due to an apology that lacked policy changes and compensation for victims, proving that apologies for historical injustices must be substantive, involve an acknowledgment of harm, and lead to change.

Some may argue that focusing too heavily on a nation's past mistakes will weaken national unity, prevent progress if a constant cycle of shame remains perpetuated, and foster a culture of resentment, guilt, and purposeless national shame. However, this assumes that shame is inherently destructive when, in reality, shame can be used as a tool for growth if it is recognized and understood, but pride built on denial cannot. The problem is not the presence of shame but when that shame lacks substance and direction. Passive shame is unproductive, whereas shame can be a powerful catalyst for change. Only by acknowledging its past and accepting accountability can a nation cultivate genuine national pride.

By facing our history, we allow for progress toward the future. It is harmful to set the precedent that false narratives and the silencing of voices are how a nation should uphold its legacy. We cannot take pride in something we refuse to accept and understand, as pride cannot be selective, but by confronting history, we create purposeful pride that fosters hope and honors the future. We have the power to end this manipulation of history now by not taking pride in false histories crafted to manipulate society and ourselves, but rather by facing the brutal realities of global history and committing ourselves to truth, to change, and to progress so that future generations when asked, "Should anyone be ashamed of their nation's history? Should anyone be proud of it?" They can say, free from the burden of false narratives, "I can be proud."

Bibliography:

Baldwin, James. "As much truth as one can bear." New York Times Book Review 14.2 (1962).

Brown, E. Caitlin. "Narratives and Memory: The Nanking Atrocity." (2018).

Calhoun, Craig. "Nationalism and the Contradictions of Modernity." Berkeley Journal of Sociology 42 (1997): 1-30.

Govier, Trudy, and Wilhelm Verwoerd. "The promise and pitfalls of apology." Journal of Social Philosophy 33.1 (2002).

Graham, Christopher A. "Lost Cause myth." Parks Stewardship Forum. Vol. 36. No. 3. 2020.

Hopkins, PJ Cain-AG, and Peter J. Cain. "British imperialism." Crisis and Deconstruction 1914-1990 (1993): 298.

Idris, Fazilah, et al. "The role of education in shaping youth's national identity." Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 59 (2012): 443-450.

Itabashi, Takumi. "The Past and Politics: Focusing on 'Vergangenheitsbewältigung' in Post-War Germany." Japan Review 2.1 (2018): 14-18.

Kitamura, Minoru. The politics of Nanjing: An impartial investigation. University Press of America, 2007.

Lorcin, Patricia ME. "Imperialism, colonial identity, and race in Algeria, 1830-1870: The role of the French medical corps." Isis 90.4 (1999): 653-679.

Pei, Minxin. "The paradoxes of American nationalism." Paradoxes of Power. Routledge, 2015. 153-159.

Stanley, Elizabeth. "Evaluating the Truth and Reconciliation Commission." The Journal of Modern African Studies 39.3 (2001): 525-546.

Vanthemsche, Guy. Belgium and the Congo, 1885-1980. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Voerman, Jan. "The Reign of Terror." Andrews University Seminary Studies (AUSS) 47.1 (2009): 7.