Cycles of Confinement: The Historical Roots and Modern Realities of Black Incarceration in America

Article by: Presley Frank / Graphic by: Jillian Hartshorne

Black Americans represent 13% of the U.S. population but account for approximately 37% of those incarcerated. They are imprisoned at roughly five times the rate of white Americans, despite comprising a much smaller share of the population. This disparity persists across federal, state, and local levels, reflecting deep structural inequities within the criminal justice system. These patterns carry profound consequences for Black communities across generations. The disproportionate incarceration of Black Americans is not the result of inherent criminality but rather a direct consequence of systemic racism rooted in slavery, reinforced by historical policies like Black Codes and Jim Crow laws, and perpetuated by racial bias in modern policing and sentencing. Understanding this crisis requires tracing its origins to the systems deliberately designed to exploit and control Black Americans.

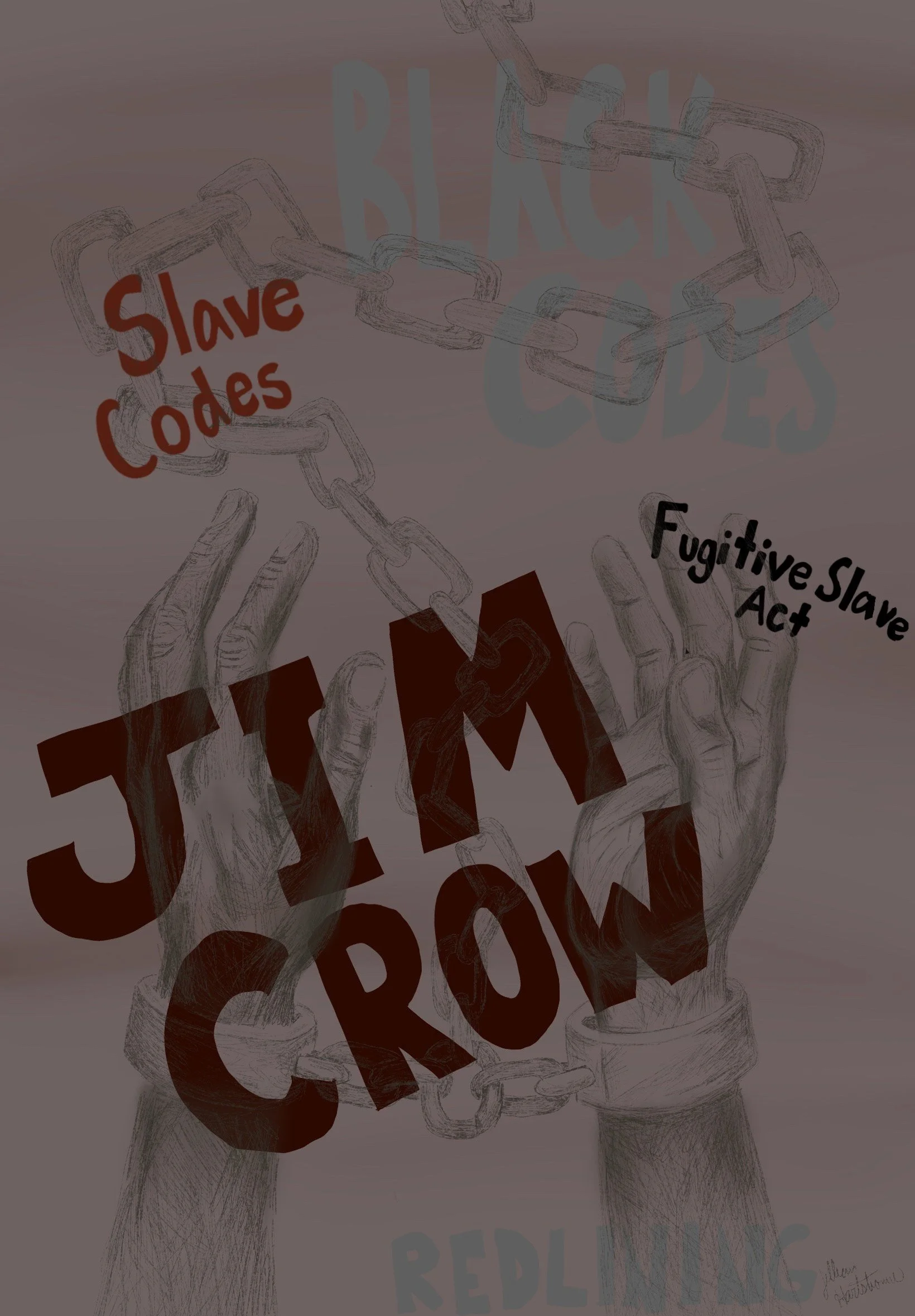

The abolishment of slavery in 1865 did not bring freedom; it cultivated an opportunity for new mechanisms of racial control. The 13th Amendment’s exception clause–permitting involuntary servitude “as punishment for crime”–provided a legal pathway to re-enslave Black Americans through incarceration. Southern states quickly began to exploit this clause by enacting Black Codes: laws criminalizing unemployment, “vagrancy,” and other vague conditions that disproportionately targeted newly freed people. Black men and women were arrested for minor or fabricated offenses and leased to private companies, plantations, and mines through convict leasing systems, enduring harsh conditions and forced, unpaid labor. These practices maintained the racial hierarchy and economic exploitation of the pre-Abolition South.

The Jim Crow era perpetuated these patterns of criminalization into the 20th century. Segregation laws made daily life a legal battlefield by criminalizing ordinary acts such as sitting in the “wrong” section of a bus a crime for Black Americans. Law enforcement became an instrument of white supremacy, enforcing racial hierarchies through arrest, intimidation, and imprisonment. Incarceration became not only a punishment, but a means of suppressing Black autonomy and political power. Though the Civil Rights Movement dismantled explicit segregation, the systems of racial control it confronted did not disappear, laying the groundwork for the mass incarceration that persists today.

Economic inequality among Black Americans today stems from centuries of discriminatory policies. Redlining denied Black families homeownership and opportunities to build wealth; underfunded schools limited educational advancement; and employment discrimination restricted access to stable careers. These systemic barriers fostered economic marginalization that directly fuels disproportionate incarceration rates. Communities experiencing concentrated poverty face heavier police surveillance, increasing the likelihood of arrest for behaviors overlooked in wealthy, white neighborhoods. The consequences of imprisonment span generations as children of incarcerated parents are statistically more likely to experience poverty and incarceration themselves, perpetuating cycles of instability. The system punishes instead of rehabilitating, trapping many Black Americans in a cycle that is social, economic, and carceral.

Modern disparities in incarceration reflect racial bias embedded throughout the criminal justice system. Over-policing in Black communities results in higher rates of stops, searches, and arrests that are often unrelated to actual crime rates. Police brutality represents the most extreme manifestation of this bias: the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Michael Brown, and countless others exemplify how systemic racism turns routine encounters into life-threatening events. Sentencing disparities further deepen these inequities; for example, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 established a 100:1 ratio between crack and powder cocaine, meaning possession of 5 grams of crack carried the same sentence as 500 grams of powder cocaine. Crack was more prevalent in Black communities and powder cocaine among white users, resulting in a law that disproportionately targeted and punished Black Americans, fueling mass incarceration during the War on Drugs. Although the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 reduced the ratio to 18:1, the enduring impact of the original policy continues to reinforce racial disparities in sentencing today.

Richard Wright’s Native Son (1940) captures the psychological and social realities underpinning this system. The novel follows the life of Bigger Thomas, a young black man living in Chicago, whose life is constrained by poverty, racism, and fear. When Bigger accidentally kills Mary Dalton, the daughter of his wealthy white employer, he is sentenced to death. Wright’s novel exposes the devastating effects that systemic racism and poverty have on African Americans, emphasizing that oppressive social conditions can drive people into desperation, crime, and violence. Thomas’ fate was written out for him before he had the chance to write his own story, and he became a product of the conditions in which he was born. Bigger’s story is not an isolated tragedy, but rather a reflection of how structural oppression molds Black existence. Native Son reveals a failure by American society to protect natural rights, illustrating how systemic racism not only punishes Black crime at disproportionate rates but also manufactures Black criminality.

Mass incarceration continues to devastate Black communities through felony disenfranchisement, employment discrimination, and the erosion of families and communities. Formerly incarcerated individuals face lifelong barriers to voting, housing, and employment, directly deepening poverty and exclusion. Black men bear the heaviest burden, being incarcerated at 5.5 times the rate of white men–a reflection not of higher criminality, but the cumulative racial bias embedded in all parts of the system. Yet, there is growing momentum for reform: movements advocating for economic justice, equitable representation, and criminal justice reform are challenging the corrupt foundations of this system. Change requires a fundamental reimagining of public safety by prioritizing community wellbeing over punishment and recognizing mass incarceration as a form of violence itself.

The disproportionate incarceration rate of Black Americans represents the enduring legacy of slavery, sustained through centuries of policies designed to control and exploit Black communities. From convict leasing systems of the post-Reconstruction South to over-policing and discriminatory sentencing today, the chain of racial injustice remains unbroken. This crisis was not created by individual choices but by deliberate systemic design, and understanding this history is essential to dismantling it. Public safety and democracy cannot coexist with racial injustice. Until America reckons with the systems built to suppress Black freedom, “justice for all” will forever remain out of reach.

Bibilography:

Blackmon, Douglas A. 2008. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. London: Icon.

Ghandnoosh, Nazgol. 2023. “One in Five: Ending Racial Inequity in Incarceration.” The Sentencing Project. 2023. https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/one-in-five-ending-racial-inequity-in-incarceration/.

Martin, Eric. 2017. “Hidden Consequences: The Impact of Incarceration on Dependent Children.” National Institute of Justice. March 1, 2017. https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/hidden-consequences-impact-incarceration-dependent-children.

Muller, Christopher. 2018. “Freedom and Convict Leasing in the Postbellum South.” American Journal of Sociology 124 (2): 367–405. https://doi.org/10.1086/698481.

NAACP. 2025. “Criminal Justice Fact Sheet.” Naacp.org. NAACP. 2025. https://naacp.org/resources/criminal-justice-fact-sheet.

Odin, Julianne. 2025. “Guides: Black and Brown Lives Matter: Cases of Police Killings and Assaults: Introduction.” Lawlibguides.sandiego.edu. April 22, 2025. https://lawlibguides.sandiego.edu/policekillingsandassaults.

Palamar, Joseph J., Shelby Davies, Danielle C. Ompad, Charles M. Cleland, and Michael Weitzman. 2015. “Powder Cocaine and Crack Use in the United States: An Examination of Risk for Arrest and Socioeconomic Disparities in Use.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 149 (April): 108–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.01.029.

Prison Policy Initiative. 2020. “Racial and Ethnic Disparities.” Prisonpolicy.org. 2020. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/research/racial_and_ethnic_disparities/.

Sabol, William. 1989. “Racially Disproportionate Prison Populations in the United States an Overview of Historical Patterns and Review of Contemporary Issues.” Contemporary Crises 13: 1989.

The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. 2021. “It’s Time to End the Racist and Unjustified Sentencing Disparity between Crack and Powder Cocaine.” The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. November 30, 2021. https://civilrights.org/blog/its-time-to-end-the-racist-and-unjustified-sentencing-disparity-between-crack-and-powder-cocaine/.

The Sentencing Project. 2018. “Report to the United Nations on Racial Disparities in the U.S. Criminal Justice System.” The Sentencing Project. 2018. https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/report-to-the-united-nations-on-racial-disparities-in-the-u-s-criminal-justice-system/.

Wright, Richard. 1940. Native Son. New York: Olive Editions.